By Duo Dickinson

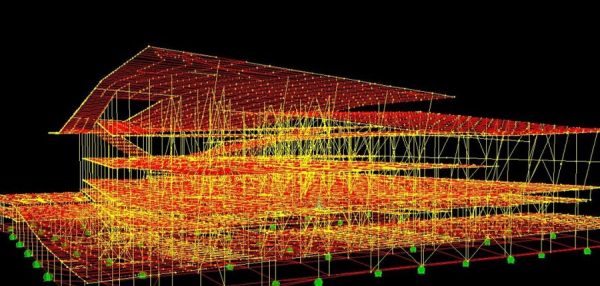

Featured image via buildapedia.com.

For most architects today, Building Information Modeling (BIM) is the elephant in the room. We know BIM and Revit take the efficiencies of CAD drawings and launch them into a near seamless technological integration of the entire design/build process that will ultimately change the way every architect works.

But change is always hard. Especially change that is both not chosen and involves alien technologies. Involuntary change causes great fear and often angry rejection. When huge machines began to eliminate artisanal labor in 1811 textile mills in England, some radical rejectionists began smashing those machines—Luddites, named for a possibly apocryphal young textile worker, Ned Ludd.

I may be closer to Ned Ludd than I want to admit. I am 61 and cannot draw a line in Autocad, let alone Revit. My firm has been CAD-centric for the 21st century, but my job description has not changed since I founded my firm in 1987. I scribble, communicate with clients and builders, visit sites and redline my staff’s CAD drawings (derived from my scribbles). Most of my contemporaries had to make the choice to dive into the CAD world themselves or spend money to have others do it.

It’s now Round 2: the BIM Moment.

Given the scale and rapidity of these changes, it’s easy to be nostalgic. Nostalgia is usually delusional, and when nostalgia mixes with the fear of the unknown, “the good old days” can be an excuse to “Make America Great Again.” In architecture the permanent resizing of expectations post-2008 crash has had a collateral depressant: another new way buildings are designed, spec’d, and even built. Some say this BIM wave has had more impact on design and construction than any seen in the last two millennia.

Clearly, this technological revolution has cost jobs, just as it did in textile mills in the 1800s. Beyond the fear of underemployment, or simply not having the newly required skills to be hired, there is a professional undercurrent that BIM’s impact on the creativity and value of the built product has been hurt by the latest round of technological tools.

Clearly, this technological revolution has cost jobs, just as it did in textile mills in the 1800s. Beyond the fear of underemployment, or simply not having the newly required skills to be hired, there is a professional undercurrent that BIM’s impact on the creativity and value of the built product has been hurt by the latest round of technological tools. Despite the quiet desperation and uneasiness in many small firms headed by older architects, there are zealots in the cause of The New Way, especially in larger firms. Architect Randy Deutsch has written profusely about the BIM’s virtues as “a convergence of buildings as data,” essentially seeing buildings as “databases.”

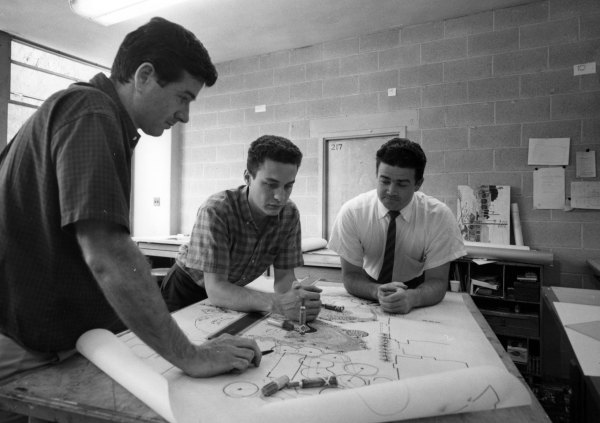

However, the old guys, being old guys, are not so sure. The late Michael Graves lamented the “lost art of drawing” in the New York Times. Yale had a 2012 symposium “Is Drawing Dead?” David Ross Scheer has written “The Death of Drawing,” a book that declares this change in means and methods greater than anything experienced in 500 years (since the creation of the Master Builder Architect in the Renaissance). He warns of a “pervasive social and cultural movement towards virtualization and predictive control through digital simulation” that will compromise the reality of built structures.

In ZDNet, CC Sullivan writes that BIM is becoming part of governmental policy to reduce our carbon footprint. McGraw/Hill notes that BIM is being imposed on architects by their consultants. Unlike CAD—which was a new language that made communication and revision so much easier, but followed an architect-centered mode of project execution—the fundamental shift to treat “Buildings As Data” has transformed the role of architects in the design/build process.

It’s a world turned upside down, where the role of the designer has been subsumed by the tools used. When combined with a fully cloud-based world of instantaneous universal data sharing, this new era of design-as-data makes the human touch seem quaint and retrograde.

The virtues of extreme data integration are obvious: infinite and instantaneous autocorrecting of structural, mechanical, material specification, oversights, even cross-referencing zoning and building code compliance. You would think all architects who are designers (instead of technicians), would be as giddy as architect Bob Borson, who wrote in 2011 that architects should “love the BIM” because “mastering the process…leads to exceptional results, both aesthetically and financially.”

Here is where I have grave concerns. Financially, those at the edge of the new technology can benefit from its efficiencies, just as early adopting CAD firms and consultants did for that technology’s first decade. But less time spent in creation always, ultimately, brings billables down to their actual worth, once the rest of the competition gets just as fast and productive as the front-runners.

The unknowable rub is aesthetics. There are unending examples of deadly dull, unthinking, schlock-stock design getting the Revit/BIM gloss that is often more than enough for a zoning board or time-sensitive client to sign off on, simply because the presentation seems legitimate and professional. The endless spam of BIM and Revit consultants heralds a time when a tiny percentage of creative humans out of the hundreds of thousands of professionally degreed architects will actually lead the techno-herd of “Building As Data.”

It’s inevitable that the extreme distillation of the “creative” side of architecture will morph architects into becoming consultants for the BIM building design industry. Architects will be further pushed into the fashion, graphic and fine arts worlds of hands-off design, further detached from culture, construction, and context.

It’s inevitable that the extreme distillation of the “creative” side of architecture will morph architects into becoming consultants for the BIM building design industry. Architects will be further pushed into the fashion, graphic and fine arts worlds of hands-off design, further detached from culture, construction, and context.

I am sure the most intensely devoted design-driven practitioners will still make exquisite expressions of architectural genius, but the vast majority of buildings will become like the vast majority of fabric: mass-produced, elsewhere, by machines, vs., say, a tiny percentage still loomed in some town in Vermont…

To the outsider (me), there is a palpable sense that BIM manifests a high-tech dumb-down of design when buildings are ripped out of the architect’s loving hands into a software design machine. Perception is one thing, but will BIM-built buildings actually be “worse” than those done in the “traditional” methods we all got used to in the 1990’s? Probably not at the low end, where low-budget hack work has historically made lousy outcomes on every level: durability, efficiency, and aesthetics. Universal standards of data integration will likely mean more competency in generic building production.

The highest level of design: “signature,” “starchitected” buildings have already greatly benefited from BIM—sculpture can be built with a minimum of miscalculation when the BIM program crosses all the T’s and dots all the I’s.

It’s the middle class of architecture, the custom designed modest structures, like Louis Sullivan’s exquisite local bank branch offices or Paul Rudolph’s Temple Street parking garage in New Haven that will simply cease to have value in the BIM machine product’s land of easy answer, high-competency mediocrity.

This proposed $60-million parking garage in New Haven is the architectural equivalent of a book-without-an-author. Image via New Haven Register.

Before you say I am just a Boomer Luddite in the sad whine of being passed over by the super-charged Gods of Progress, consider Connecticut’s Department of Transportation, proposing a $60,000,000 parking garage for New Haven, essentially on the BIM model when there is an entire little city of hungry architects to choose from. Embodying the shallow mindlessness of click-it-into-place computer glossed construction, the scheme is literally a meme: an undesigned collage of components masquerading as a building.

Whenever things change, something is lost. The cuteness of our babies gives way to their surly adolescence, but ultimately the surliness gives way to the goodness of the adults most humans grow into. I am sure BIM and Revit will create a new bottom line of competency in construction. But I do not want my children to just be competent—I want them, all of them, to be beautiful.

This article originally appeared on commonedge.org and is published here with permission.

About the author:

Duo Dickinson has been an architect for more than 30 years. His eighth book, “A Home Called New England,” will be released later this year. He is the architecture critic for the New Haven Register and writes on design and culture for the Hartford Courant.

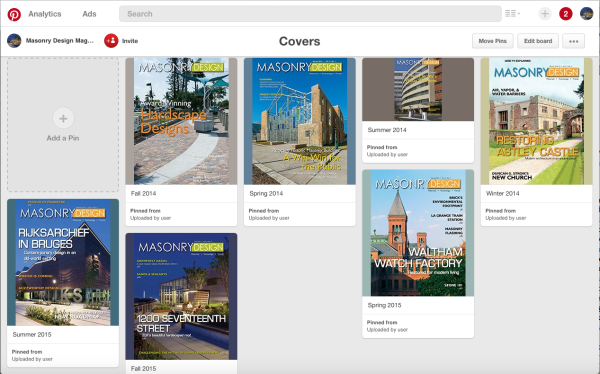

There’s a great deal of hype and hyperbole surrounding social media and its efficacy to business. There’s an endless supply of experts to tell us that if we’re not “social” then our businesses are as good as dead. And there are an almost endless number of social media outlets clamoring for our content—and presumably our ad dollars, or at least our contact information. But there also are stacks of data to support the premise that your business could die a slow death if you’re not active on social media.

There’s a great deal of hype and hyperbole surrounding social media and its efficacy to business. There’s an endless supply of experts to tell us that if we’re not “social” then our businesses are as good as dead. And there are an almost endless number of social media outlets clamoring for our content—and presumably our ad dollars, or at least our contact information. But there also are stacks of data to support the premise that your business could die a slow death if you’re not active on social media. I’m a college student. Studying masonry. That’s “how I work.” When I’m asked what I’m majoring in at college, most people do not expect to hear the word “masonry” come out of my mouth. Half the time, I can’t tell if they are surprised that I’m willing to bust my butt doing masonry work, or shocked that I am actually going to a college to learn the trade of becoming a skilled mason. Either way, that’s just “how I work.”

I’m a college student. Studying masonry. That’s “how I work.” When I’m asked what I’m majoring in at college, most people do not expect to hear the word “masonry” come out of my mouth. Half the time, I can’t tell if they are surprised that I’m willing to bust my butt doing masonry work, or shocked that I am actually going to a college to learn the trade of becoming a skilled mason. Either way, that’s just “how I work.” I’m excited to be a part of the next generation of masons. I don’t know where the industry might be in 10 years, but I know that the industry is evolving every day. I hear the talk of robots coming into our lives, replacing our jobs. Specifically, replacing my job as a mason! Yes, to an extent, robots are capable of doing what a basic mason can do. But when I say basic, I mean basic, non-intricate masonry projects that involve a repetitive succession of simplistic motions. No robot is going to be able to build you a genuine Rumford fireplace inside of your household. No robot is going to be able to individually chisel, trim, and meticulously lay stone on the exterior of your chimney. No robot is going to be able to make a multi-skew cut on a brick for your intricate Gothic arch way. For as long as I may live, no robot is going to put me out of a job.

I’m excited to be a part of the next generation of masons. I don’t know where the industry might be in 10 years, but I know that the industry is evolving every day. I hear the talk of robots coming into our lives, replacing our jobs. Specifically, replacing my job as a mason! Yes, to an extent, robots are capable of doing what a basic mason can do. But when I say basic, I mean basic, non-intricate masonry projects that involve a repetitive succession of simplistic motions. No robot is going to be able to build you a genuine Rumford fireplace inside of your household. No robot is going to be able to individually chisel, trim, and meticulously lay stone on the exterior of your chimney. No robot is going to be able to make a multi-skew cut on a brick for your intricate Gothic arch way. For as long as I may live, no robot is going to put me out of a job. I encountered two situations on social media recently that illustrate the new dangers construction and design firms face regardless of whether they participate as a company. Did you notice that I said regardless? This is a critical issue for all AEC firms that creates risk 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

I encountered two situations on social media recently that illustrate the new dangers construction and design firms face regardless of whether they participate as a company. Did you notice that I said regardless? This is a critical issue for all AEC firms that creates risk 24 hours a day, seven days a week.